“Slow down or Perish: the economics of degrowth” is the title of the book written by Timothée Parrique which establishes new bases for thinking about society differently. Let's take the exercise one step further.

On December 13, 2022, a conference entitled “Slow down or Perish: the economics of degrowth” was masterfully presented on the subject of the book of the same title by its author, Timothée Parrique, French economist and researcher at the Lund University, in the premises of HEC-Liège.

His economics work is accessible to all and criticizes the pursuit of the idea of infinite growth as deleterious to our social cohesion and accelerating ecological collapse. He offers us the bases of a system of “degrowth”, or “post-growth”, starting with the criticism of the traditional development indicator, GDP.[i].

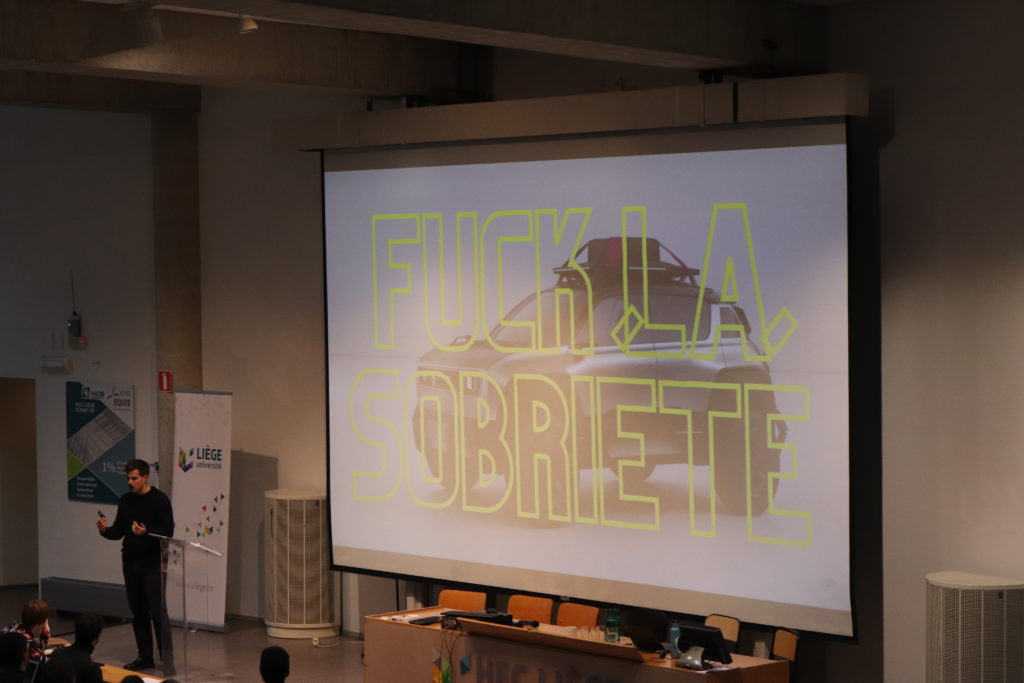

Indeed, our economic model is built around a hypothesis often accepted as an axiom: economic growth leads to an increase in the quality of life. This hypothesis justifies the appearance of numerous contemporary economic and productivist phenomena: overexploitation of resources, planned obsolescence, globalization, extractivism, fast-fashion... All these concepts have in common that they contribute to economic growth; and therefore theoretically to well-being. However, we realize that this parallelism between growth and well-being is only a myth which seems to have established itself as a tangible and indisputable reality.

However, the field of research is increasingly interested in alternative indicators of development[ii]. The aim is to be interested not only in the increase in industrial production in a territory, but to try to integrate the notions of well-being, health, environment and social development, and this to a more global scale. Many scientists are looking into the issue and have developed numerous alternative theories or systems integrating these different aspects, such as for example Isabelle Cassiers and her work “Towards a post-growth society: integrating ecological, economic and social challenges”, or Kate Raworth with “The Donut Theory, the economy of tomorrow in 7 principles”, or even Dominique Méda with “The Mystic of growth: how to free yourself from it”.

Let us now imagine a world where we would have applied the principles of degrowth developed by Timothée Parrique: refocusing on our well-being, directing the consumption of resources in order to return within the limits of their renewal, redefining indicators for sustainable development and no longer simply productivist. Let's imagine a world where we took the time to redefine our own personal needs instead of having them dictated to us by marketing. Let us look at the more global consequences that such a way of life would have on our society.

What would a sober society look like?

In an imaginary "sober" society, in "post-growth" or "degrowth" (choose your preferred name, noting that certain names can have a more negative connotation than others), from the author's imagination of this text and being only one of the many possibilities, our daily way of life would very closely resemble that which we have in the real world. After having gone to school to follow our basic education, we would then specialize in a profession that we want to join, we would then work trying to maintain a balance with our family and private life, and we would then be at the retirement where we would live happy days. We would have access to quality health and education systems, and we would be able to flourish in the pursuit of our hobbies in our free time.

In fact, the differences do not appear in the broad outlines of our lives, but in the small details of everyday life. For example, we would perhaps no longer have an individual washing machine, but shared with our neighbors, in a common laundry room. We would travel to our place of employment primarily by public transportation, and we would have a primarily remote working regime, to encourage limiting travel. We would no longer need the car to go to commercial areas to do our daily shopping, but a network of local stores would allow us to not have to travel several kilometers to obtain our basic necessities. The electronic devices we use would no longer be designed to be thrown away and quickly replaced, but could be kept for decades, easily improved and sometimes passed on to the next generation; in the event of a breakdown, we would not throw our device in the garbage, but we would have access to a repair circuit allowing us to put it back in order at a lower cost, as well as to documentation databases allowing us to carry out the repairs ourselves when possible.

New homes would no longer be built with a logic of lower cost, but based on materials with a much greater longevity.[iii]. We could still go wherever we wanted on vacation, whether by car, train, bus or plane, but our frequency of use of polluting transport would be reduced as much as possible, through a voluntary change in our travel habits or by a system recording our trips; so we could consciously fly to our dream destination at the end of the world, but we couldn't do it several times a year.

What changes on a daily basis?

In reality, our life would not change enormously, and our comfort of life certainly not. The goods we would consume would be the same, as would transportation, but they would probably be more expensive. The designs of housing, electronic devices, our vehicles, our clothing and many other goods would be improved to maximize not the profit of the producing company, but the utility they provide to consumers. Thus, a smartphone would not have a lifespan of two or three years with a reduced price, but would have a lifespan of around ten years, with the possibility of repairing it, and the purchase price would be much higher to encourage maintenance rather than replacement. This would not, however, be to the detriment of employment in productive industry, because places would be created in the maintenance industry. The efforts of manufacturers would therefore no longer be directed towards reducing costs or increasing the quantity of goods produced, but rather towards improving technologies, durability and product efficiency.

Not all areas would be impacted. Reducing our waste of energy and raw materials in our consumer goods would not prevent us from continuing to use them for scientific research, for health services or for defense. It wouldn't be about taking these decisions to the extreme and going back to the Middle Ages, but rather about using what we have responsibly. Instead of throwing our resources away for the benefit of a minority, they would be rationalized and used where they would have the most impact for the common good.

This new societal approach would have the direct effect of being able to control environmental impacts, not only in terms of pollution generated by the different industrial sectors, but also in terms of greenhouse gases emitted. With a stabilization, or even a reduction in the energy we consume, we would have an easier time increasing the share of renewables in the energy mix. The major challenges of a society in transition[iv] and with a more rationalized economy would be the maintenance of our democratic process (by not falling into the trap of granting decision-making powers to different experts and technocrats) and the good distribution of impacts and changes in habits between the most deprived and the most fortunate.

Conclusion

Obviously, this view of the mind is a theoretical exercise, and therefore does not correspond to any present reality. However, it is interesting to indulge in it, because it allows us to put our lifestyle and consumption choices into perspective with what contributes to our happiness. Infinite growth, whether green, sustainable, or social, corresponds to a myth because it is located in a world with finite resources. The task may seem immense and can easily be blamed on others, on government or on business, but our critical efforts would lead us to concrete and collective actions, which would in turn influence political and economic directions in a radical way, and we ourselves would be the big winners from this change.

Arthur Longrée.

[i] GDP: Gross Domestic Product, economic indicator used to measure wealth creation over a fixed period.

[ii] For more details on this subject, “What if the economy told us about happiness? », by Laure Malchair, available on the Justice & Peace website: https://www.justicepaix.be/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/2013-CJP_etude_economie-du-bonheur_texte.pdf

[iii] Roman buildings are still standing after several millennia, and we have to demolish ours after around fifty years. This should be a source of emulation for our construction professionals

[iv] For more information on this theme, “What ecological transition for tomorrow? Energy, Climate, Metals” in three parts on the Justice & Peace website: https://www.justicepaix.be/quelle-transition-ecologique-pour-demain-energie-climat-metaux-partie-1/