Currently, many regions of the world are devastated by violent climatic events. However, rich countries are often less severely impacted. Faced with this injustice, COP 27 of 2022 finally recorded the establishment of a background of losses and damages aiming for international financial support and solidarity to help with reconstruction.

image credit: pexels: pok-rie

Entre le mois de juin et novembre 2022, le Pakistan a connu la mousson la plus dévastatrice de son histoire. Au mois d’août, une quantité d’eau jusqu’à 7 x supérieure à la normale s’est abattue sur le sud-est et le centre du pays. Cette catastrophe a fait au moins 1 700 morts, affectant 33 millions d’habitants, détruisant 250 000 habitations et 1,8 million d’hectares de terres agricoles. Le dommage financier était estimé en janvier 2023, à plus de 30 milliards d’euros , juste pour les conséquences économiques directes[1]. To this already very high bill must be added the costs linked to indirect consequences (possible epidemics, destruction of agricultural areas, etc.).

The disaster in Pakistan is one of many examples of extreme weather events appearing in different regions of the world in recent years. Hurricanes, droughts, floods have affected countries in the North and the South in 2022 with much more violence than before.

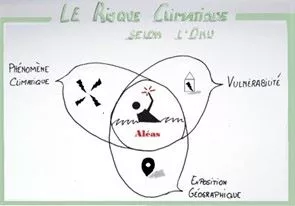

Climatic hazards, between vulnerability and geographic exposure

The IPCC final report of March 20 The last one, which summarizes the previous reports, is clear about the anthropogenic origin of the phenomenon: it is now the entire planet and the living things it shelters that are affected by this climate emergency that we are causing. However, these risks – also called climatic hazards[2] – do not mark territories in the same way : a period of drought in France does not have the same consequences as a drought in the Horn of Africa. The effects will be more devastating and lasting depending on their geographic exposure and vulnerability.

The explanation as to geographical exposure of the affected location is quite simple: we are not impacted in the same way by a flood on the banks of a river or two hundred kilometers from the shore. On the other hand, for the vulnerability, there are several factors which take into account the capacity of the territory to cope with the shock due to the climatic phenomenon itself and its negative impact in the longer term such as, for example, the socio-economic context (level of development , resources, developed infrastructure, access to resources, etc.), the political situation or the cultural context[3].

A glaring injustice in the face of climatic hazards

Considering all the countries of the world, still according to the IPCC report, we know that between 3.3 and 3.6 billion human beings live in conditions highly vulnerable to climate change. Given this logic of the three pillars of climate risk, these people live in developing countries – mainly the poorest among them – and in small island states.[4]. This time again and unsurprisingly, the richest countries are the most resilient in the face of climatic hazards while the poorest countries often have the most difficulty recovering from these disasters.

Furthermore, the cumulative cost of short-term damage is today estimated by the IPCC between 300 and 600 billion dollars per year, and this is for the economic cost alone because this is obviously without taking into account the loss of biodiversity. , places of high cultural and historical value, and the forced relocations, migrations and other psychological trauma that populations undergo. Scientists have estimated that this economic range could be valid until 2030 but that this amount will increase thereafter due to the worsening frequency, intensity, duration and geographic extent of climatic hazards.[5].

Therefore, how will these southern countries, which are already so vulnerable, be able to pay the bill for the damage without falling into even greater debt in the long term? Alone, it's impossible. The pill of this inequality is all the more difficult to swallow when we know that rich countries are responsible for half of the cumulative greenhouse gas emissions since the beginning of the pre-industrial era. while weighing, in terms of population, only 12 % of Humanity.

Faced with this observation, three solutions are available to us: first, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, second, make territories more resilient to shocks (upstream, therefore) and third, allow territories to quickly repair the damage caused.

COP27 or how to act on the symptoms and not the causes of the crisis

Sommes-nous tellement aveuglés et endurcis que nous ne pouvons plus apprécier les cris de l’Humanité ? It is with these words that the Prime Minister of Barbados Mia Motley addressed the heads of state at the opening of COP 27 in Egypt in November 2022[6]. During her speeches at COP 26 and 27, she called on heads of state – and those of developed countries in particular – to take their responsibilities in terms of “repairing” the climate damage that is being caused.

Today, if the question of taxing fossil fuels (the main causes of GHG emissions) still remains a taboo in international discussions, COP 27 in 2022 tackled reparations for the first time by recognizing the need to financially help the most vulnerable countries to cope with the damage caused by global warming.

On the table since the 1990s, this “climate debt” owes its existence to the alliance of small island states (AOSIS). It will be necessary to wait until 2013 for the Warsaw International Mechanism acknowledge this request [7], 2015, for the Paris agreements to confirm it and, 2022 – the shock of the floods in Pakistan and Mia Mottley's speeches at COP26 and 27 – so that this point finally appears concretely in the negotiations[8]. This (too) long delay is due to the difficulty for rich countries to assume a historic responsibility for developed countries but also to the fear that recognition of the existence of a climate debt towards developing countries development will open the door to risks of legal proceedings and other potential demands for compensation.

On the night of December 19 to 20, 2022, the president of COP 27 calls for a vote on this issue of loss and damage. She is adopted. It was a general surprise because this point was not even on the agenda of COP 27. It was added at the request of the European Union which changed its mind, followed by the States- United. Although this solution – the only real progress made by CO27 – is still totally insufficient, it is an international step forward which must be welcomed.

What does a loss and damage fund actually mean?

At this stage, this fund is still an empty shell because the agreement does not provide anything regarding the details of payers and beneficiaries.

Who will it be for? Since the notion of vulnerability is not defined, it is believed that at least the “Least Developed Countries (LDCs) – a group of 46 countries listed by the UN based on GDP and IDH – but also the small islands of the Pacific which are already seriously threatened by rising water levels will be able to benefit from it. However, it is more complicated because, if we take the case of Pakistan, for example, it was – at least, before August – not part of the two categories of countries mentioned above.

Par qui sera-t-il alimenté ? Les pays les plus développés seraient les plus légitimes à alimenter ce fond. Mais, depuis le début des années 1990, plusieurs pays émergents se sont enrichis et ont émis beaucoup de gaz à effets de serre. La Chine, par exemple, qui est aujourd’hui le premier pays émetteur de GES au monde, a rattrapé les autres pays pollueurs en se plaçant à la seconde place de la quantité de GES émise cumulée depuis l’ère préindustrielle. Quant aux entreprises, que pourrions-nous en attendre alors que certaines sont très émettrices et ne payent même pas leur part fiscale ? Là encore, rien n’est inscrit aujourd’hui. Actuellement, les versements se font sur base volontaire : douze gouvernements tels que l’Écosse, la Wallonie (qui avaient toutes deux déjà versé de l’argent avant la COP27), l’Allemagne, le Canada, ou la Nouvelle-Zélande ainsi que l’Union européenne ont promis de débloquer au total, environ 360 millions de dollars. En outre, des organismes tels que la Banque mondiale, le Fonds monétaire international (FMI) ainsi que des banques de développement sont également mobilisées. Un groupe de réflexion a pour mission de donner corps à ce fonds en lui donnant une existence législative aboutie d’ici la future COP 28 de novembre 2023 à Dubaï. Les ONG plaident, de leur côté, pour l’ajout de financements innovants qui pourraient par exemple provenir de taxes sur les transactions financières, l’extraction des énergies fossiles ou sur les émissions des secteurs aérien et maritime[9].

Today, we are still a long way from achieving solidarity from the countries of the North towards the countries of the South but despite everything, with this first recognition of a responsibility of the countries of the North towards the countries of the South and, if this is made effective, of the implementation of a taxation of activities emitting high GHGs, the kick-off was given towards a more important reflection. Moreover, on March 29, the General Assembly voted for the intention to request an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on the obligations of States with regard to climate change[10]. This is a great reason to remain optimistic!

Laura Didier.

[1] GEO, Pakistan: flood toll threatens to rise with diseases, UN says 21.09.2022, https://www.geo.fr/environnement/pakistan-le-bilan-des-inondations-menace-de-grimper-avec-les-maladies-selon-lonu-211829.

[2] We call climatic hazard Or climate risk tout évènement climatique ou d’origine climatique qui est susceptible de se produire (avec une probabilité plus ou moins élevée) et qui peut entraîner des dommages sur les populations, les activités et les milieux.

[3] OECD, Manage climate risks and deal with loss and damage, March 2022, 410 pp.

[4] Small island developing states (SIDS) refer to a heterogeneous group of island territories, mostly located in the Caribbean, the Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean.

[5] IPCC (2021d), Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. (eds.), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, in press.

[6] Mia Mottley, Prime Minister of Barbados at the Opening of the COP27, World Leaders Summit, UN Climate Change, Sharm El-Sheikh.

[7] The Warsaw International Mechanism was established in November 2013 at COP 19 to address loss and damage related to the impacts of climate change, including extreme weather events and slow onset events, in developing countries particularly exposed to harmful effects of these changes.

[8] OECD, Op cit.

[9] Boughriet R., COP 27: what the unprecedented agreement on loss and damage provides, Environmental news, 11/22/2022.

[10] The General Assembly requests an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice on the obligations of States with regard to climate change, Seventy-seventh session, 64th and 65th plenary meetings – morning & afternoon, G/12497, March 29, 2023.