Looting, rape, sexual slavery, displacement of populations, torture, constitute crimes committed for several decades in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) without any responsibility being established against the perpetrators. As stated by the Doctor Mukwege, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2018, the impunity that reigns in the DRC only fuels new tensions in the Great Lakes region and fuels new conflicts.

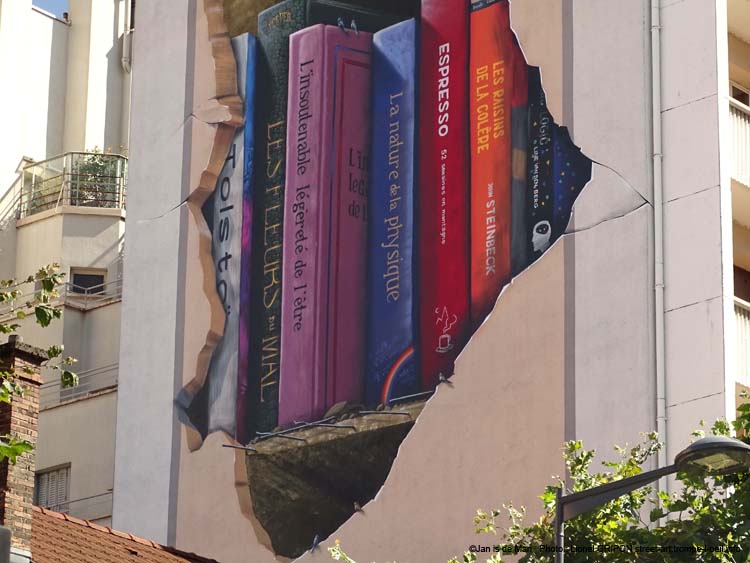

Credit: Claude Truong-Ngoc, 2015 Creative Commons Attribution – Share Alike

Since 1997, the DRC has been the scene of a series of civil wars and armed conflicts mixing ethnic and political aspects linked to the natural resources of the country, involving several border countries and several armed groups. During these conflicts, numerous massive human rights violations are perpetrated involving large numbers of movements of the civilian population across the country. The abuses committed represent the most serious crimes, also called international crimes, and affect the international community as a whole.

The Congolese national authorities persist in the almost total absence of establishing the responsibilities of the perpetrators of the abuses. The successive leaders of the DRC prefer to rely on the mechanism of obliteration Who consists of forgetting the past. It manifests itself, among other things, by the repeated execution, amnesties within the Congolese legal system. In this sense, the amnesties of 2005, 2009, 2014 and 2020 prevent perpetrators of crimes from being prosecuted before national courts and often even allows them to be offered a place of high rank within the government. For example, Jean-Pierre Bemba, a former warlord, officially took office on March 26, 2023 as Deputy Prime Minister in charge of Defense.

After decades of impunity and in a current climate of tensions and conflicts, it's time to turn towards a global system for the repression of international crimes in order to achieve pacification of the region. Although some measures have been adopted, in particular measures related to the Transitional justice, we deplore the lack of adoption of real effective measures to combat impunity in order to establish the responsibilities of the perpetrators of abuses.

However, many avenues, both national and international, are possible to combat impunity and are interconnected, although they encounter many challenges.

The failure of Congolese national courts

The principle of territorial sovereignty as well as international obligations give national courts a main role in the prosecution of the most serious crimes. Given that the crimes are committed on Congolese territory, it seems obvious that it is up to the Congolese courts to assess the content of these crimes. Indeed, evidence, victims and witnesses are at hand and greatly facilitate investigations and the holding of trials.

However, the mapping report, a report by experts commissioned by the UN on the situation in the DRC, attests that the Congolese judicial system is marked by significant inadequacies which prevent it from functioning. Indeed, the Congolese judicial system is designed in such a way that fundamental judicial guarantees cannot be respected. The Congolese judicial system faces two major problems. On the one hand, the Transparency International report concerning corruption released in 2022 declares that the Democratic Republic of Congo is ranked 166e place of the most corrupt countries on the planet out of 180. According to the NGO-DH, the richest use justice to their advantage by corrupting justice officials.[1] On the other hand, judicial decisions when rendered impartially are often victims of political or economic interference which does not allow their implementation.[2]. Justice, although it is supposed to be a means of ensuring social peace, is a new divide for the population in the DRC, which cannot trust its institutions.

Therefore, the weak means available to this judicial system to fight against impunity, and the numerous political interferences illustrate on the one hand its failure and on the other hand its lack of independence and impartiality[3].

Although several trials have been conducted, Congolese courts are not able to respond to the scale human rights violations and international crimes committed on Congolese territory. Furthermore, Congolese national courts have little chance of obtaining the appearance of people residing abroad despite the significant participation offoreign actors. This is why the fight against impunity must be established within a global system of repression including an international level.

The inadequacy of the International Criminal Court in an effective fight against impunity

The International Criminal Court is a permanent Court that was established to investigate and try the most serious crimes that affect the international community as a whole, such as war crimes, crimes against humanity, the crime of genocide and the crime of aggression . In 2002, the DRC authorities ratified the Statute of the International Criminal Court. In June 2004, the Prosecutor's Office opened an investigation at the request of the former President Joseph Kabila, first concerning the violations committed in Ituri, then the investigation was broadened and now includes the Kivu provinces. Since then, several cases have been brought by the ICC. According to the principle of complementarity enshrined in Article 17 of the Rome Statute, the Court intervenes only as a last resort, only when national courts are unable or unwilling to investigate and arrest the alleged perpetrators of international crimes. As we have seen, the Congolese judicial authorities are, to date, still not not able to offer the necessary sufficient guarantees. The ICC is therefore, the only competent court having the capacity, integrity and independence necessary to prosecute perpetrators in the commission of international crimes on the territory of the DRC.

Although a revolutionary step forward, the ICC, due to lack of structural and financial means, is not sufficient to fight against impunity in the region and does not provide adequate reparation to victims. Indeed, the Court can only exercise its jurisdiction from 2002, date of entry into force of its Statute. Consequently, all the crimes committed during the two wars that the DRC has experienced cannot be brought before the ICC. Next, the Court cannot investigate and prosecute all cases given the considerable number of violations committed. Furthermore, with regard to a self-referral from the DRC to the Court, one can question the intentions of former President Kabila concerning the instrumentalization of the Court in order to pursue only his opponents who are members of rebel groups. . Finally, again due to lack of resources, the Office of the Prosecutor is required to select the items which he is investigating. In the DRC, the Prosecutor's strategy was to focus on "second-tier" perpetrators, which may result, among other things, from a certain political opportunism.[4]. This selection can lead to great frustration on the part of the victims and even result in an aggravation of already existing ethnic tensions. For example, many questions have been raised regarding the impartiality of the Court in view of the reduced charges against Lubanga And Ntaganda in comparison to those extended against Katanga And Ngudjolo.

The inability of the ICC to exercise its jurisdiction in many respects, significantly reduces efficiency of its main mission of fighting impunity and attests to the necessary creation of new judicial mechanisms combining both national and international perspectives.

The combination of national and international authorities in the fight against impunity

To remedy the shortcomings of both the Congolese national courts and the ICC, the solution that seems most appropriate would be to turn to a mixed jurisdiction. Hybrid courts would combine Congolese national and international aspects in their composition and in their procedures[5]. They have the potential to overcome domestic obstacles such as inadequate amnesty provisions or laws granting immunity. In addition, they could contribute to strengthening of the Congolese judicial system, into a rule of law, which is less obvious with a purely international tribunal. In addition, the proximity of the victims and the communities most affected by the crimes being prosecuted allows for better efficiency. One of the advantageous practices of hybrid jurisdictions is the possibility of highlighting certain violations characteristic of the conflict. In the case of the Congolese situation, sexual violence are used as real strategic weapon, it would therefore be interesting to focus on this type of crime.

However, a risk of deference to state sovereignty may remain. Furthermore, if not carefully designed, the combination of international and national standards can also create contradictions.

Consequently, the Justice and Peace Commission (CJP) is mobilizing to obtain a global system of repression combining the strengthening of Congolese national jurisdictions, the continuity of the work of the ICC, and the establishment of a hybrid court. Together, these bodies would put an end to the culture of impunity and offer an opportunity for pacification of the region. The Justice and Peace Commission also calls on Belgian authorities to implement their universal jurisdiction to repress the abuses committed by Congolese nationals in the DRC, who are now in Belgium. Finally, the NGO supports movements which aim to contribute effectively to the fight against impunity such as campaign “Justice for Congo” in connection with the film the Empire of Silence and calls on Belgian citizens to relay these messages. It is by fighting jointly and at several levels against impunity that we can achieve a satisfactory system.

Louise Lesoil.

[1] DRC: AGOPA-DH recommends the questioning of judicial authorities for effective responses to the threat of corruption – Sauti Ya Congo

[2] Justice in the Democratic Republic of Congo: transformation or continuity? (openedition.org)

[3] Corruption in the justice sector in the Democratic Republic of Congo | by Anti-Corruption Research Center | Analysis on Corruption (anticorruption-center.org)

[4] Miscarriage of justice? The results of the ICC in the DRC | openDemocracy

[5]National Holistic Transitional Justice Strategy (panzifoundation.org)