In an increasingly connected world, information is a key element in confronting the adversaries of democracy. But what about misinformation?

On February 24, war knocked on the doors of Europe. Vladimir Putin, the Russian president, has decided to invade Ukraine. Against all odds, he faced a courageous Ukrainian president, an army determined to defend his country and civilians hostile to the Russian army, including in territories with a large Russian-speaking population. We Europeans are in shock. We grew up in a world where we thought war was a thing of the past. We have become accustomed to democratic regimes, diversity of opinions, free press, non-violence, negotiation, diplomacy and peace. However, the logic of the Russian regime is that of authority, confrontation, fear, censorship, disinformation, oppression and violence.

Since the end of the Second World War, with the exception of the wars in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, we have experienced the longest period of peace in our history. The only war we knew was this “cold war” between the Western bloc and the Eastern bloc, between Western countries and the Soviet Union, between capitalism and communism. A symbolic and almost invisible war during which deterrence and “star wars” took precedence over physical threats and armed conflict.

The terrible thing about war is that it has direct, concrete and dramatic consequences: thousands of soldiers die in combat, millions of people flee their homes and their countries, civilians are massacred, women are raped, etc. we are unfortunately witnesses once again. War is indeed the worst thing that can happen to a nation and a people.

Beyond the palpable side of this war, we also feel destabilized by the fact that, to this day, the real reasons for this conflict remain unclear. We are still seeking to know the exact motivations and final project of Putin, whose personality remains mysterious and his behavior unpredictable. And not knowing what its intentions and real plans are complicates any form of negotiation and any prospect of peace. Indeed, how can we negotiate, end the war and begin a peace process when we find ourselves faced with an interlocutor who does not hesitate to use force to achieve his ends, who lies and who almost systematically denies everything? of which he is accused. It may have been forgotten, but disinformation has been an integral part of Putin's strategy for more than two decades, both inside and outside Russia's borders. An essential ingredient for authoritarian regimes which can go so far as to destabilize institutions traditionally guarantors of peace in the world, like the UN.

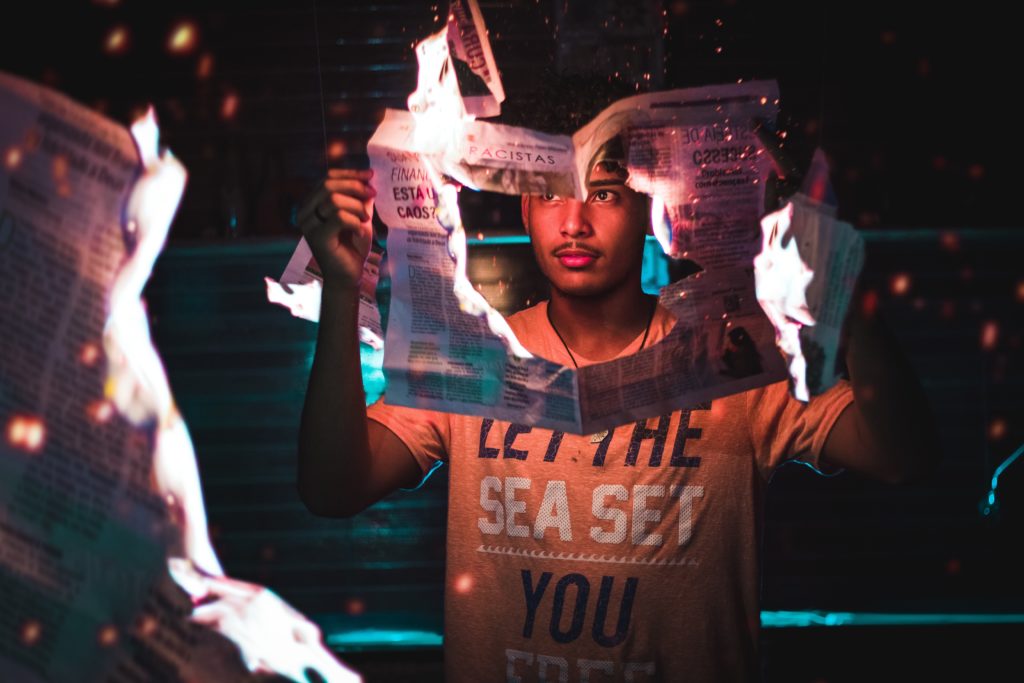

In the age of continuous information, the internet and social networks, the war in Ukraine also reminds us that behind every armed conflict there is a media war in which communication plays a crucial role. Thus, by assimilating Ukrainian leaders to Nazis, Putin can justify his “special operation” by “denazification” of Ukraine and “peacekeeping”. This also allows him to pose as a “liberator”.

Propaganda and disinformation have always been used as political and military weapons, regardless of country or period of history. Controlling information and the media means ensuring control of the population because information directly influences our thoughts, emotions, behaviors and opinions. This is why Putin controls almost all the media in his country. In the most extreme cases, disinformation can be used to trigger and fuel conflict, war or even genocide. During the genocide in Rwanda in 1994, the minds of Hutu citizens were prepared, influenced and conditioned for months, notably via Mille Collines Radio which broadcast messages of hatred towards the Tutsis. She went so far as to incite the Hutus to physically attack them and eliminate them. And to facilitate the act, the Tutsis were dehumanized by being compared to cockroaches.

This is the same type of process that was put in place for years by the Nazis to justify the extermination of the Jews. The first step was to put in place propaganda designating them as responsible for Germany's misfortunes and aiming to dehumanize them by likening them to rats that had to be gotten rid of. Prejudices which led to events as terrible as the Nuremberg laws, Kristallnacht, the Warsaw ghetto and Auschwitz. In the decades that followed, numerous works in psychology have experimentally demonstrated this reality: prejudice and dehumanization are fertile ground for discrimination and violence against a group designated as a scapegoat.

Even if Putin's objective is not to commit genocide against the Ukrainians, Russia's scapegoats are indeed explicitly designated. According to him, NATO, Western countries, the USA and the Ukrainian government threaten the interests, security and future of his country. A strategy then allows him to justify his war: that of the self-fulfilling prophecy. Indeed, one of the consequences of the war in Ukraine is the strengthening of NATO and the links between Ukraine and the West, which are supplying it with more and more weapons, which confirms Putin's initial theory. To justify his war, he therefore creates an illusion by skillfully reversing the causes and consequences, by accusing others of doing what he is doing, and by trying to make us forget that he alone decided to start this war. The prophecy is then fulfilled by following this logic of inversion: the aggressor transforms into a liberator and the culprit transforms into a victim. A fallacious reasoning that is also found in conspiracy-type thinking. In the context of the covid-19 pandemic, for example, for some anti-vaxxers, doctors were no longer considered health professionals who treated us. They had become agents of power who sought to control us and kill us slowly by injecting us with a vaccine. And at the political level, democracies were associated with health dictatorships. It is therefore not surprising that many anti-vaxxers are at the same time pro-Putin.

The disinformation surrounding the war in Ukraine also fuels another belief: the just world theory. Spontaneously, we tend to believe that what happens to a person (or a people) is justified. We have learned since childhood that “good people” were rewarded and “bad people” were punished. It is this famous popular belief according to which there would be no smoke without fire. If a young person gets beaten up by the police, it’s because they were looking for it. If a girl gets sexually assaulted, it's because she was wearing sexy clothes. If Ukraine is invaded by Russia, it is because it has been provoking it for years. Because she wants to join NATO. Because the Ukrainians are committing “genocide” against the Russian-speaking populations in Donbass. The Ukrainian regime is then compared to a Nazi regime in the pay of the Americans. This type of statement obviously serves as a pretext for war and serves to convince public opinion that this military operation is justified and therefore morally right.

Another cognitive bias comes into play: ideology bias. Most of us are convinced that we are right and that those who do not think as we do are wrong. We believe that the way we think a society should operate or the way a country should be run is the right way. In other words, that our ideology is better than that of others. In a democratic country, this bias is mitigated by the diversity of opinions and the debate of ideas. But in an autocratic or dictatorial regime, it prevents any questioning and leaves the door open to all kinds of abuses. This could explain why Putin cannot stand the fact that Ukraine, a country of the former USSR, wishes to move politically towards a Western-style democracy and turn its back on Russia. According to some specialists, this would even be the real reason for the conflict.

The plurality of ideas and differences of opinion are one of the pillars of democracy and a guarantor of peace. Danger arises when they are not respected. Even more, it occurs when we can no longer agree on the facts, when they are denied, distorted or reduced to opinions. This is called post-truth. However, authoritarian leaders, dictators and extreme parties have an almost systematic tendency to distort the facts to serve their own interests. When Russia bombs a train station and kills dozens of civilians, it accuses the Ukrainian army of being responsible. When she is accused of the Boutcha massacres, she cries out for disinformation (while decorating the soldiers who committed these abuses). Rhetoric that demonstrates the extent of Putin's cynicism. If I deny the facts of which I am accused, this allows me to act with complete impunity. If I accuse the other of abuses when it is I who committed them, this allows me to exonerate myself while legitimizing them. Finally, if the suffering of the victims is ignored and if the culprit does not recognize or take responsibility for his actions, this gives way to feelings of injustice, hatred and revenge. And it is because of all these disastrous consequences that disinformation can be considered one of the greatest dangers to peace.

David Bertrand.