After having begun to examine its colonial past in the Great Lakes region, Belgium could become one of the European leading figures in the work of memory. However, the pacification of memories will remain a wishful thinking without a real reappropriation of the debate by citizens.

The Special Commission responsible for examining Belgium's colonial past has taken the first steps towards a reconciliation of memories, but the most important thing remains to be done.

From Canada to the United Kingdom, via Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, France, Germany to Denmark, the debate on the colonial past and the possible reparation of indigenous peoples is at the forefront. agenda. Belgium has also been swept along by the wind of change. She moves forward with a slow but firm step.

As a reminder, on July 17, 2020 the House of Representatives took a strong action by creating the Special Commission responsible for examining Belgium's colonial past in DR Congo, Rwanda and Burundi. This initiative, welcomed by civil society, came in the wake of the anti-racist demonstrations and decolonial movements which marked the summer of 2020 with the controversy between supporters and opponents of the unbolting of statues bearing the effigy of King Leopold II and from 60e anniversary of the independence of the Democratic Republic of Congo. All this without forgetting, of course, the expression of King Philippe's "deepest regrets" for the "suffering" caused to the Congolese men and women during the Leopoldian period and then, in the Belgian Congo.

Certainly, this is not the first time that a special commission has been set up to investigate the role played by Belgium in the Great Lakes region,[1] but the Colonial Memory Commission is unique in its ambition and the complexity of its task.

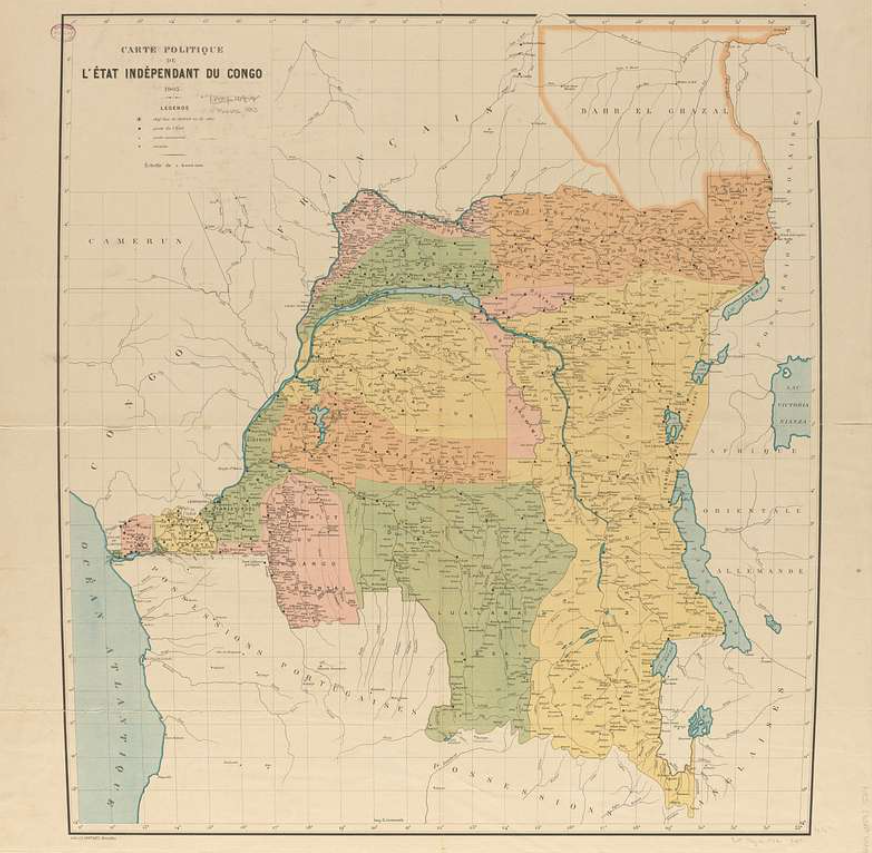

Complex, because it aims to clarify a long period which began in 1885 with the creation of the Congo Free State by King Leopold II, passing through the Belgian Congo, then by the attachment in 1919 of the territory “Ruanda-Urundi” following the Treaty of Versailles, until the independence of 1960 and 1962. Ambitious, because its ultimate goal is to create a space conducive to dialogue between groups carrying colonial memories and Belgian society as a whole, with the aim of building a inclusive, peaceful future, based on a past that is certainly painful, but common.

This summer, the Commission therefore celebrated its first candle and the duration of its mandate, unrealistic at first, was extended. At the end of October 2021, ten experts who make up the multidisciplinary committee mandated by Parliament to investigate the colonial past have officially released the fruit of their analyzes and their historiographical work.

No less than 689 pages, accessible on the Chamber website, collect the individual and collective contributions of experts, who have devoted themselves to studying the archives of one of the most decisive periods in the history of the Kingdom. Let us cite here some of the themes addressed: systemic violence and brutality caused during the colonial enterprise, the grabbing of land and goods, “identity brutalizations”, categorizations and prejudices, racism, the contribution of the colonies to the Belgian war effort (1914-1918), forced labor, exploitation...the list goes on!

The experts also made numerous recommendations[2], including the restitution of looted objects; “the payment of a pecuniary colonial debt in the face of the moral responsibility of Belgium”; the establishment of “a national commemorative day for the victims of colonization” or a national colonial history month; “put an end to collective amnesia” thanks to an education system stripped of concepts inspired by old colonial propaganda and put in place measures against racism.

The report was generally well received by parliamentarians and the French-speaking press, who praised its quality and rigor without denying the element of subjectivity that can sometimes appear depending on the positions and areas of expertise of the committee members. However, certain gray areas were raised, such as the omnipresence of the DR Congo compared to Burundi and Rwanda, as well as an insufficient analysis of the role of the Church. Furthermore, the report is resolutely incriminating against the former colonial administration. This did not fail to arouse reactions from those who regret the omission of certain effects of colonization which they consider positive. The construction of infrastructure and schooling return to the top of the list.

Although these criticisms should be taken into account in the future in an inclusive analysis of other experiences and perceptions of the colonial fact, it should be remembered that the experts had a mandate based on the search for responsibilities; in other words, on a rigorous examination of the facts and consequences of Belgium's colonial past and on the consequences “that should be taken”.

The work of the committee of experts is of undeniable importance, but it is not an end in itself. This is rather a first step in an inevitable journey whose end we cannot guess. This is where the challenges, the gropings, the doubts lie, but also the great interest of this approach to working on memories. Because finally, it is only by moving forward that our eyes will be able to dissipate the fog.

Currently, the members of the Parliamentary Commission have just started a series of hearings with representatives of the diaspora, not to debate or question them, but to hear them in all the diversity of their experiences. .

Between “living memories” and indifference

Sixty years may mean little to those who lived through the colonial period and the independence of Congo, Rwanda and Burundi. Where some see humiliation and domination, others see a “paradise lost”.[3] This feeling was also strongly nourished by colonial propaganda according to which the Belgium of yesteryear willingly carried out a civilizing mission and fought the obscurantism of indigenous peoples to put them on the path to emancipation.[4]

When the years pass, while certain facts become blurred in memory, emotions remain like an indelible imprint. It is from emotions that memories draw their power, to the point that they can be transmitted from generation to generation while retaining their essence, even among those who have never experienced them.

In Belgium, we have long witnessed a phenomenon of emotional disinvestment from colonial history. Not only did it seem to be relegated to a limited number of interest groups including former colonials, the African diaspora, researchers and diplomats. But also, the Belgian colonial power was based on exploitation, so that the population viewed this enterprise with relative distance.[5] With the exception of executives and employees of the administration, among others, who settled for a period determined by the exercise of their functions. This interest was, therefore, very different from that aroused by the settlement colonies.

Today, for a vast segment of the population, young or not, moreover, sixty years that have passed are equivalent to bygone times like a history book made of blank pages.

In this context, sometimes of silence, sometimes of questions, making the link between colonization and contemporary racism is for some a difficult exercise. However, it emerges from a study financed by the King Baudouin Foundation in 2017[6] based on a sample of 800 Belgian citizens of Congolese, Burundian and Rwandan origin, that a large majority of Afro-descendants are in favor of taking memorial measures linked to colonial injustices. Among them, 74% believe that colonial history is under-represented in public debate and 91% of the interviewees think that it should be taught more in schools.

These findings were confirmed by the report published in August 2019 by the Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent of the United Nations Human Rights Council, after a field visit.[7] He concludes that “the root causes of contemporary human rights violations lie in the lack of recognition of the real scale of the violence and injustice of colonization. » In the process, the UN called on Belgium to “confront and recognize” the role played by King Leopold II and the long-term impact of colonization both on Belgian territory and on the Greater Region. Lakes.

The imperative to decompartmentalize the debate on the colonial past

As the creation of the Special Commission in the Chamber proves, the awareness and the desire to develop real work on memories is becoming more and more evident, but it must not remain a purely political affair. This desire must pass through schools.

The Minister of Education of the Wallonia-Brussels Federation, Caroline Désir, is also committed to the decolonization of new history standards. Their implementation is planned for 2026 for the 1st secondary schools, 2027 for the second and 2028 for the third secondary schools. [8] For its part, the Belgian associative sector is a model of self-criticism by adding the decolonization of their institutions in the five-year program 2022 – 2026.

We have also seen a clear revival of interest in the colonial question on the part of the population since last summer. However, a colossal challenge still remains: to ensure that the various memories of the Belgian colonial past leave their niches, that they free themselves, that they speak in the forums of the State and establish themselves permanently. on school benches. “Living memories” which enter homes without knocking on the door, which are embedded in newspapers, which permeate art and culture. Memories which are not afraid to take the opposite path, which sometimes get lost, which often dialogue, get confused, struggle, catch their breath but never fall asleep. This is not a rhetorical or political question. It is the antidote against denial, trivialization, against the overvaluation of “colonial work” or indifference. This is the recipe for our memories to come back to us.

To achieve this (let us allow ourselves to dream), transparency in all the work carried out by the Commission must be essential. As said above, all voices of memory bearers must be heard, whether or not they are aligned with the perspective of the majority. A thirst for dialogue is palpable today; we must not miss this momentum through fear of conflict.

Each federated entity of Belgium must commit body and soul to transmitting the colonial past to future generations through education. It is therefore essential to create spaces in school programs conducive to the appropriation of this subject by teachers. According to the French historian Pascal Blanchard, “the concern is that states are letting teachers deal with colonial memory without having themselves resolved how to deal with the issue”.[9]0r, it is by giving young people the tools to see, judge and act that we can have a social project focused on the future.

In addition, the government should take into account the recommendations of civil society organizations which also claim their place in the debate as agents of change. Finally, the Commission must continue to give the Congolese, Rwandan and Burundian diasporas a special place so that they can actively participate in the process of reconciling memories and in the fight against racism.

In short, all segments of society must seize this moment to work as a team and to prove that there is truly strength in unity.

In 20 years, what seeds will have grown in the earth we are excavating? One thing is certain: future generations will gauge our efforts by the value of their heritage and, hopefully, will continue to enrich the land of their elders.

Alejandra Mejia Cardona.

[1] DEBEVE, Clara, “On the need to think about the Belgian colonial past in Central Africa”, Justice and Peace Commission, December 18, 2020. Link: https://bit.ly/3tfVK1V.

[2] See page 685 of the experts’ report

[3] GILLET, Florence, “Congo dreamed? Congo destroyed…The former Belgian colonials grappling with a society in repentance. Investigation into the emerged side of a memory", in The History of Present Times notebooks, n°19, 2008, p. 79-133.

[4] KLEIN, Olivier and LICATA, Laurent, “Interviews on a common past: former colonized and former colonials facing Belgian action in the Congo”, in SANCHEZ-MAZAS, M. and LICATA, Laurent. “The Other: Psychosocial Perspectives”, Presses Universitaires de Grenoble, 2005.

[5] BAZAN, Ariane, KLEIN, Olivier, LUMINET, Olivier, ROSOUX, Valérie and VAN YPERSELE, Laurence, “Belgium – België. Crossing of languages, histories and memories”, in Memories at stake, p. 120 – 130, No. 3.2017.

[6] ADAM, Ilke, DEMART, Sarah, GODIN, Marie, SCHOUMAKER, Bruno, “Citizens with African roots: a portrait of the Belgian-Congolese, Belgian-Rwandan and Belgian-Burundians”, Report, King Baudouin Foundation, 2017.

[7] “Media statement from the United Nations Human Rights Council Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent”, Belgium Report, 2019.

[8] BURGRAFF, Eric, “(De)colonization: the history references are already rewritten, but not yet taught”, The evening, June 10, 2020. Link: https://bit.ly/3g7ckgs.

[9] “Colonialism: from the “civilizing work” to the time of reckoning”, Le Vif/L’Express (Special issue), June 2021, p.118.