Who hasn't heard of at least one company-related scandal? Precarious and dangerous work, child labor, displacement and poisoning of populations, tax evasion, financing of armed groups… The list of human rights violations committed directly or indirectly by multinationals is long and worrying. Just like the line of victims demanding justice. Citizens are paying the price of companies, which have become more and more powerful and less and less controllable, including by States. Faced with this impunity resulting from numerous legal obstacles, will the treaty currently being negotiated at the United Nations (UN) on corporate responsibility finally be the solution?

- Recognize the primacy of human rights on commercial and investment law through a responsibility of all companies (not just transnationals);

- Apply to all sectors (minerals, textiles, agri-food, etc.) and all the rights recognized, including ILO international labor standards;

- Detail all the stages of the duty of care by providing a special emphasis on preventive measures ;

- Include extraterritorial obligations in order to prevent a company from taking advantage of its “multinational” character to escape justice;

- Recognize the corporate criminal liability in national penal codes;

- Protecting whistleblowers and human rights defenders ;

- Shift the burden of proof onto companies : currently, it is up to the victim to prove the existence of damage, the fault causing it and the causal link between the two. Given the obvious difference in resources, it would be fairer if the stronger party, therefore the company, bears the burden of proof;

- Facilitate access to justice by reducing the costs of procedures and create a fund financed by signatory states to help the poorest victims file a claim for compensation.

- Find out about the brand, origin and production conditions of what I buy. Possibly boycott certain brands known for violating human rights. For example, the NGO achACT website (http://www.achact.be/) and the “Fair Fashion” application contain interesting information on clothing companies;

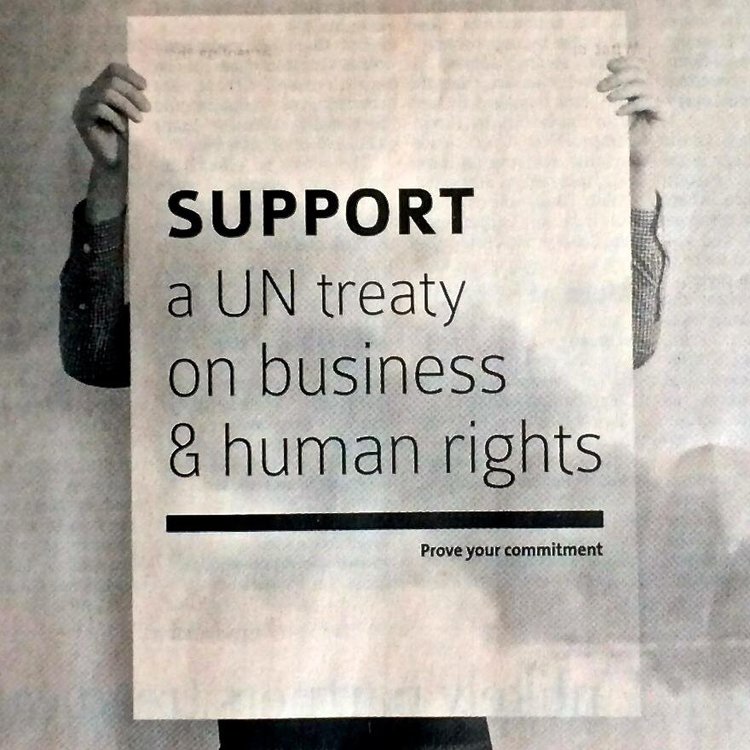

- Sign the UN Treaty Alliance petition;

- Exert pressure on political leaders by sending an email or a letter to the Minister of Foreign Affairs. Justice and Peace can provide models for this purpose;

- Make noise, talk about it around me, with family and friends, share the information on social networks.

Attachments

Notes[+]

| ↑1 | New free trade treaties increasingly protect investors, now allowing them to sue a state before an arbitration court. To get an idea: there are currently more than 700 arbitration cases pending and each one costs an average of $8 million in legal fees. See on this subject David E. and Lefèvre G. (2015), Juger les multinationales, Mardaga-GRIP. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | According to the latest Oxfam report on inequality, in 2017 82 % of wealth created benefited the richest 1 % of the world's population, while the 3.7 billion people who constitute the poorest half of the humanity received nothing. |

| ↑3 | The UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights has noted a significant increase in killings, attacks, threats and harassment against human rights defenders who speak out against businesses. |

| ↑4 | For a more detailed case study, see Blackburn D. (2017), Removing Barriers to Justice – How a treaty on business and human rights could improve access to remedy for victims, ICTUR. |

| ↑5 | These “soft law” rules live up to their name. |

| ↑6 | The Responsible Mining Report of 2018 shows for example that out of 30 mining companies analyzed, only half have formally committed to aligning with the UN Guiding Principles. And only 30 % actually have systems in place to assess risks and prevent negative impacts on human rights. |

| ↑7 | Every year, more than 100 million mobile phones are abandoned in Europe after having been used for only a few months. |